The First Rule of Holes: If You’re in One, Stop Digging

Perhaps more than any other, oil is an iconic energy source. We use lights, heating, and cooling on a daily or hourly basis, but for most people, oil (in the form of gasoline) is probably the only actual fuel we ever really handle. We see gas prices every time we fill up our cars (or drive past a gas station), and for those of us old enough, there are memories of the 1970’s oil crises when there were long lines at gas stations. Our connection to oil is so strong that rising prices can damage our economy and influence presidential elections. Not coincidentally, politicians at almost all levels have some position on where, how, and whether we should keep digging for the stuff.

Oil Markets: Not the Fun Kind of Roller Coaster

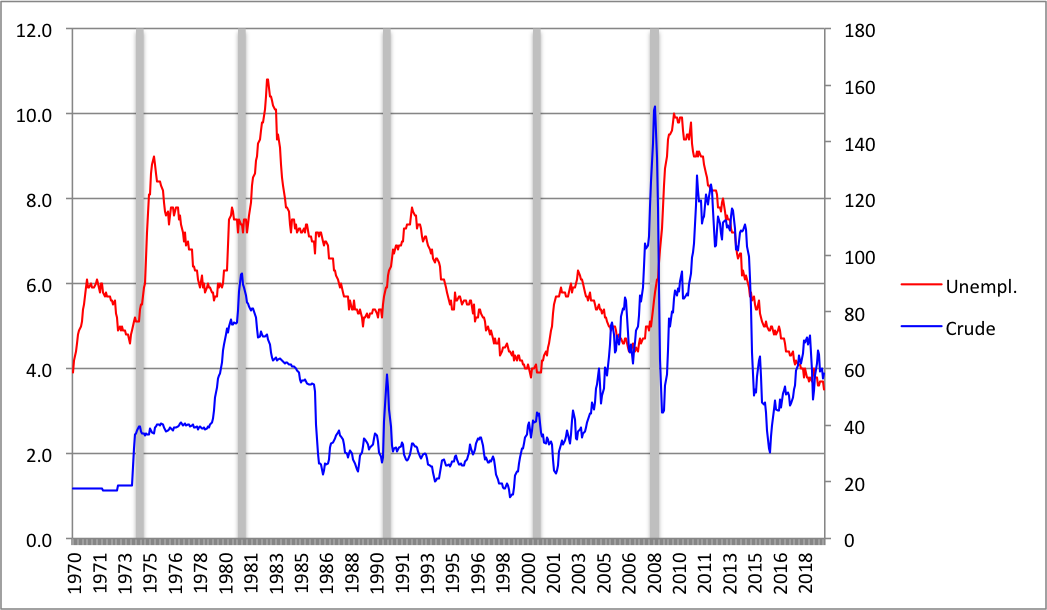

Previously, I tried to explain that the economic problem with our dependence on oil is not so much with high oil prices but with rapidly increasing oil prices. The data shows pretty clearly that we can have low unemployment when oil prices are either high or low, but when prices jump steeply, then unemployment tends to jump in response. Of course, no one likes high oil prices, but if prices are high and steady, at least we can plan for it; we’ve had stretches of high oil prices and falling unemployment. On the other hand, if prices are low and they suddenly double, all the planning and investment that was based on oil prices being in one neighborhood can become uneconomical almost overnight. The havoc oil prices can wreak on our economy is clear from one of my favorite charts that shows the unemployment rate (on the left) and oil prices per barrel (on the right):

The ability of oil prices to whipsaw our economy combined with the fact that we import lots of it gave some people the idea that the solution was to increase domestic oil production. “Drill Here, Drill Now” was a pretty popular slogan in the 2008 election. Someone even made a song out of it.

Unfortunately, as is so often the case, catchy political slogans don’t make for good policy.

We’re Already in Deep Enough

There are a few essential problems with trying to drill our way to oil independence. The first is that oil prices are set on a global market. It flows out of a relatively small number of countries to meet demand all over the world. It’s something of an over-simplification, but it’s helpful to imagine all of the buyers and sellers meeting somewhere in the middle of the ocean. Buyers bring money, sellers bring oil, and whoever offers the most goes home with a full tanker. The point is that nationality doesn’t have any influence on prices. Specifically, American oil producers don’t sell oil to other Americans at a discount just because they’re all Americans.

Another problem is that in this world of globally set prices, American producers act as what economists call “price takers.” Which means more or less what it sounds like, i.e. that American producers look at what oil is selling for (or predicted to be selling for) and decided how much oil to produce accordingly. This is not true for other major players in the oil market. OPEC, Saudi Arabia in particular, and Russia look at where oil prices are, where they would like them to be, and how they might change their production to push prices in the direction they prefer. The reason for this that the Russian and OPEC governments can essentially control how much oil their countries produce. American oil production, on the other hand, is determined by how much oil all the individual producers decide to make. So while Russian and OPEC production levels are set with a mix of economic and geopolitical targets in mind, American oil companies set their production at the levels they think are in their individual self-interests.

Are We at the Table or on the Menu?

To see why this matters, we only need to take a look at history, going all the way back to March and April of 2020. Before the COVID-19 pandemic really took hold, oil prices were falling, and Russia and Saudi Arabia had failed to agree on oil production limits to prop up them back up. Russia decided to increase production, and the price slide continued. Rather than cut production on its own, Saudi Arabia decided that it too would increase production and push prices even lower in an attempt to punish Russia economically and force them back to the bargaining table. Prices were on their way further down when the pandemic hit and oil demand crashed over night. Prices plunged even further, and Russia and Saudi Arabia got back together over Easter weekend and agreed to steep production cuts, of about 10 million barrels per day, almost a quarter of the combined OPEC and Russian output.

And who was notably not part of that decision? The largest oil producing country in the world: The United States. Though the Trump Administration worked through diplomatic channels to help make this deal happen, it didn’t actually agree to reduce oil production for the simple reason that it can’t. The U.S. government has no control and little direct influence over the production decisions of the 10 or so major oil companies and the literally thousands of smaller ones that produce together produce the vast majority of American oil.

So you can see the problem: No matter how much oil American companies produce they can’t move prices to suit their own economic interests, far less American strategic geopolitical goals. In the best of times, this leaves our economy vulnerable to volatile swings in global oil prices that are often unpredictable and always uncontrollable. In the worst of times, it leaves us vulnerable to deliberate manipulation by other global powers using their oil production as a strategic geopolitical tool.

How Do We Get Out of the Hole?

So what’s a country to do? We’ve tried drilling our way out of this. We became the world’s largest oil producer, and it didn’t help. Drilling less doesn’t help either. If supply isn’t the answer, then we should take a hard look at demand. The unfortunate truth is that as long as we are heavily dependent on oil, we will be vulnerable to oil prices.

One obvious approach is making our cars and trucks more efficient. The less gas we need to go a mile, the less impact gas prices have on us. Unfortunately, we seem to be moving in the wrong direction on this. Maybe even more obvious is to stop using oil in our cars altogether, or at least broadening our options. Electric cars still need energy, of course, but since we use almost no oil for electricity generation, we would at least be free of the volatility and geopolitical manipulation that oil prices subject us to. Even options like flex fuel vehicles that can run on either ethanol or gasoline would give us the option to avoid oil prices.

All of these alternatives have their challenges. How do we make enough batteries for fleet of electric cars? Perhaps more importantly, how do we dispose of them? Ramping up ethanol production, particularly from corn, has serious implications for the agricultural sector, and the amount of energy that it takes to make ethanol might be more than it’s worth. No matter what option we choose, there are pollution and climate impacts to think about, all of which makes increasing efficiency look increasingly attractive.

At the end of the day, the point is that if we want to free ourselves from the economic consequences of oil price volatility, we have to free ourselves from oil. This is one hole we can’t drill our way out of.